Wrestling with ethics in foresight practice?

Personal reflections, a conversation with Wendy Schultz

An ask…

… this is really me coming to you and saying, can we have a community conversation about this?

Because I don't think we talk about it enough? I don't think we talk about ethics enough in terms of the individual in the particular, and the localized.

I think, as as people engaged in futures practice and futures research, and to some extent in foresight to take not only a creative approach to our exploring futures but a systemic approach and a critical approach. And I think the more we think systemically and critically, the more we get into that space of asking not just what are the impacts of change. but what are the both the intended and unintended consequences of change? Both change that other people make, or other parts of the system make but changes that we ourselves make as part of adapting to the sea of change.

So there's that question of accountability and responsibility for those intended and unintended consequences. And there is also that critical set of questions about and how do those? How do the consequences and the impacts of changes, the changes we make and the changes to which we're adapting. How do those impacts cascade out? whom do they affect? And how?

I think the critical issues especially are important when we are talking about the disempowerment and marginalization of different communities of life on the planet, not just humans, but other communities of life as well, and and also internally, how we are disempowering ourselves, perhaps, by not being mindful of different patterns of thought within our own heads.

Starting with her PhD Dissertation Defence

Wendy Schultz reflects on her dissertation defense, vividly recalling the committee, which included notable figures such as urban planner M. Lowry, futurist Jim Dator, and anthropologist Michael Hamnett, among others. Her dissertation, she notes, was more of a "methods textbook" than a traditional academic work. It explored how futures studies and research contribute to leadership, particularly in the context of transformational and visionary change. It drew from various real-world projects in Hawaii, the Pacific Island nations, and state government, offering a comprehensive guide to conducting foresight projects—from horizon scanning to impact assessment, scenario creation, and strategy formulation.

During the defense, the challenging question came from political leadership expert Glenn Page. He found her work valuable as a practical handbook for political and community leaders but raised an unexpected ethical question: “What if Hitler had gotten a hold of this?” Wendy grappled with this, noting that Hitler had indeed used visionary leadership to offer a compelling future that attracted followers, though with devastating consequences. She pondered the ethical dilemma of powerful tools for change being potentially misused. This led to a broader reflection on how future visions can either foster hope and societal resilience or contribute to destruction. Wendy emphasized that positive, hopeful images of the future are essential for societal survival, while dark, pessimistic visions could be damaging.

She also shared a conversation with a community leadership practitioner who revealed that she deliberately chooses not to help those she believes are doing harm, a decision that highlights a tension between ethical considerations and the practical need to earn a livelihood. Schultz extended this tension to working with corporations in a capitalist system, questioning how one balances ethical concerns with the realities of making a living in a world dominated by capitalist incentives.

The anecdote closes with her musing over these ethical dilemmas, still wrestling with the question of who should have access to such powerful transformative tools.

Balancing Personal Values and Team Integrity

Wendy Schultz shares an ethical dilemma she faced when approached by a former colleague who had transitioned from a futures consultancy to an in-house futurist role at a large organisation, which she subtly implies is connected to the tobacco industry. Wendy, personally affected by the harmful consequences of smoking, particularly the death of her father from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, was naturally hesitant due to her personal history with the industry.

The colleague was not from the marketing or sales department but from research and development, and they were interested in exploring what lies "beyond tobacco."

This raised a practical ethical question for Wendy:

should she engage with an industry she believes has caused harm?

For her, the key consideration became whether the organization was genuinely moving toward a less harmful space. If they were seeking to reduce harm, Wendy felt inclined to support that transition.

However, another layer of complexity arose from her leadership role as a co-founder of a company. It wasn’t just about her personal ethical stance toward the client, but also about how her decisions would impact her team. She realized that the ethics of the situation extended beyond the client’s actions—it was also about her responsibility to her team and ensuring that they, too, could make ethical judgments.

This prompted a broader conversation within her company about handling ethically complex clients, particularly when team members come from diverse cultural backgrounds with different values and trade-offs.

The team ultimately devised a "rule of thumb": they would only consider clients or projects that aligned at least partially with their mission of benefiting both people and the planet. Additionally, they created a mechanism allowing any team member to express discomfort and opt out of working with a client if they felt ethically compromised.

Wendy emphasized that this approach ensures that the ethical decision-making process respects not just her personal values but also the diverse ethical perspectives within her team.

Exploring Ethical Challenges and the “Rules of Thumb”

Wendy facilitated the discussion and participants were prompted to contribute their ideas on a Miro Board https://miro.com/app/board/uXjVLZrP9Q4=/

“To begin the workshop, let's explore the ethical struggles we face in futures practice. The aim is to collect stories and engage in an ongoing conversation about the challenges and dilemmas we encounter. Through these discussions, we hope to uncover some informal "rules of thumb" or guiding principles for ethics in futures work. Additionally, we’ll also delve into the ethical dimensions of the futures we envision or promote, as this is another crucial aspect of our practice.”

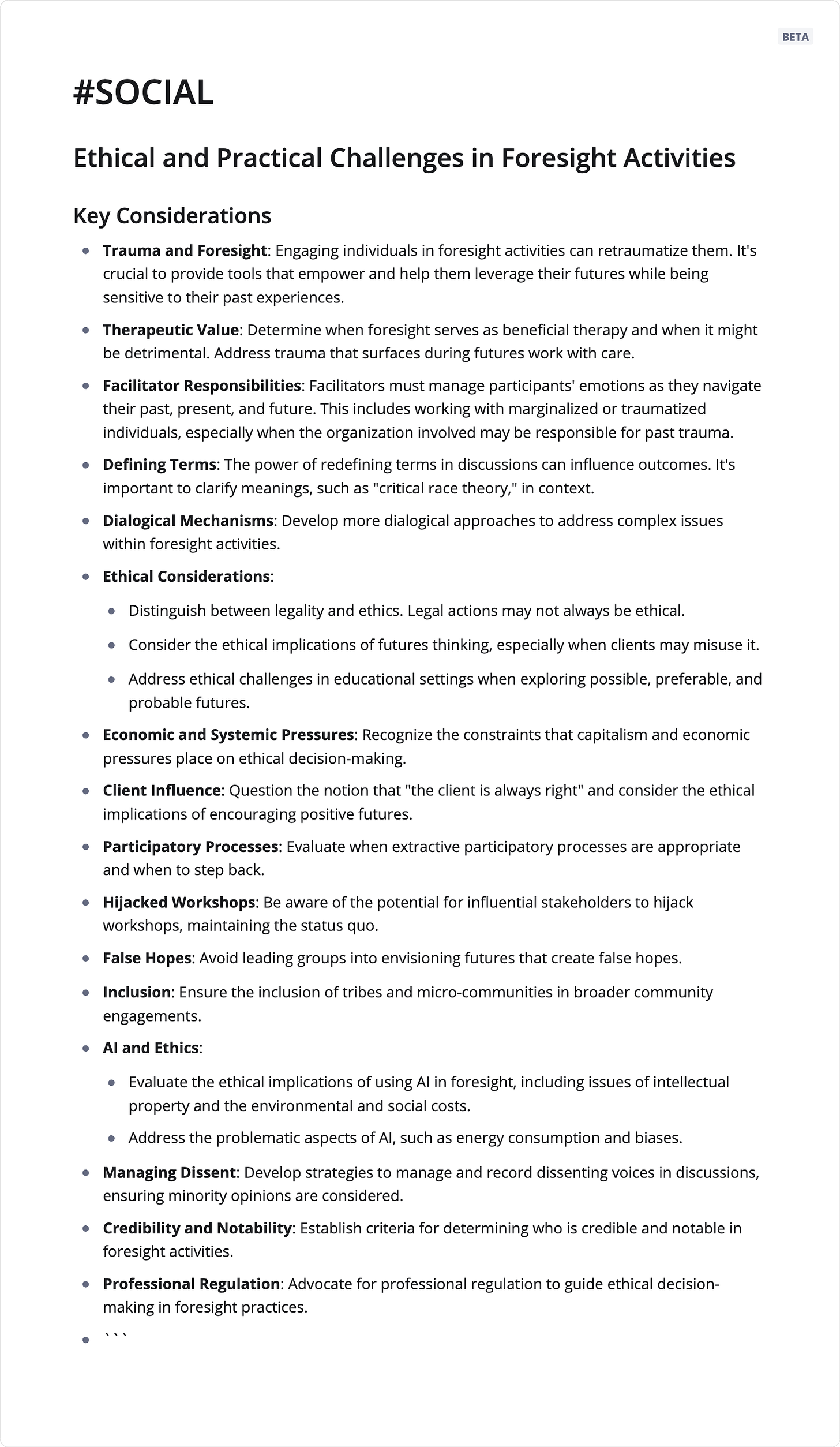

Clusters of ideas emerging from the workshop

Next Steps…

Missed the workshop?

Listen to the recording here

JFS Monthly Meet

We meet once a month. Our meet is a casual get together - just a space for like-minded people to hang out and talk about Futures. We welcome members to host our monthly meet and talk about topics they’re mulling over, or invite guest speakers.

This is an experimental space. If you wish to give a short talk, try out a workshop or just have a casual discussion about a certain topic, feel free to email Anisah or Lavonne Leong

We publish materials for futures studies here on Substack.

This is an ever-expanding library of futures thinking teaching tools that will eventually include skills and dispositions from all over the world. These resources range from semester-long curricula to exercises that can be done in an hour or less. They are for many ages and stages of readiness, and can be used by anyone.

If you have created a tool for teaching futures thinking and want to add it to our community resource pool, please reach out to us on LinkedIn.

If you are not sure where to start, let one of us know, and we’ll make a suggestion.

JFS Futures Community has a YouTube channel and a LinkedIn page

JFSCoP Youtube

JFS LinkedIn

Community Space on Discord